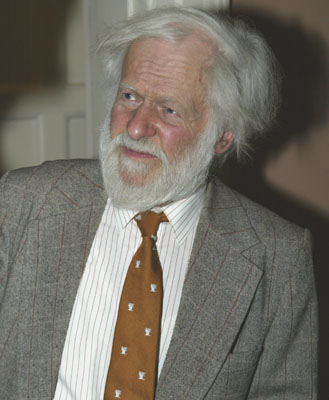

Christopher Wallis in April 1983, on the day of the windmill's opening ceremony.

Christopher Wallis in April 1983, on the day of the windmill's opening ceremony.

If you ever met Christopher Wallis, I am sure that you will never forget him. He might have been describing how he could restore your dilapidated historic building. He might have been showing you why your historic building had already been ruined by an unsuitable conversion, or telling you how it could have been put to better use. You could have heard him putting his determined point of view on any conservation or transport matter at a meeting, never afraid to speak his mind, whoever he was addressing. You could have met him while he was at work on a mill or any historic structure. You could have sat in the front row at a talk about traditional carpentry skills, and found that Christopher's adze showered you with wood shavings.

Christopher was born on May 1st, 1935 and lived his early years at Effingham in Surrey. He was the youngest of four children, who were joined by two adopted cousins after their own parents had died. Christopher's father was Sir Barnes Neville Wallis. Being the youngest child, Christopher spent time alone with his parents, once all his elder siblings were away at boarding school. He would have grown up seeing his father working all hours, and even in his earliest years, Christopher gained a fascination for timber and carpentry. At the age of 12 he was sent to Dauntsey's School near Devizes in Wiltshire. After school, he went to University College London, but a motorbike accident (from which it took him a year to recover) prevented him from completing his degree.

He obviously felt that he had to start working, and he chose the subject which would remain the fundamental basis for his work during the rest of his life - Civil Engineering. He first worked for British Railways as a railway engineer. Having an office in Brunel's Paddington station in the late 1950s would surely encourage anyone's interest in the historic environment. He continued his studies part-time at Westminster College.

Christopher left BR in 1960 and after some travelling, he wanted to get more involved with timber, and went to the Timber Research and Development Centre at High Wycombe. Here he not only received a qualification from the Institute of Wood Science, but he also met Barbara, who was a timber technician. However, he needed to gain a wider knowledge of civil engineering and moved to Reading Borough Council, and later to one of the largest civil engineering contractors. This gave him scope to become involved in various types of projects. Local ones included bridges on the M40 motorway, and even the cooling towers of Didcot Power Station. He attained membership of the Institution of Civil Engineers, which had been an ambition for a long time.Christopher and Barbara had married in the early 1960s, and had settled in Little Marlow. This gave him his first important building restoration project, restoring their run-down cottage into a family home, where they had two children, Humphrey and Amy.

The family joined the Chiltern Society in 1966, only the year after it had been founded. Christopher soon got involved and became a local footpath warden. In this role, he drew the first Chiltern Society footpath map, which would lead to the legendary series of maps that are still flourishing, 40 years later.

In reading the Chiltern News, he saw that Christopher Barry (then Chairman of the Historic Works and Buildings Group) was interested in Lacey Green Windmill. Christopher Wallis read that mill experts had been to see the windmill and had declared it impossible to restore.

The 'experts' claimed that the only way to preserve the unique 17th century wooden machinery of Lacey Green Windmill would be to move it to a museum. Such a statement was obviously a challenge to Christopher. By then, having returned to British Railways in 1969, he was working as a bridge engineer at Paddington. He persuaded a colleague that they should visit the windmill and see for themselves why it was 'impossible to restore'. On studying it, he used his engineering skills to devise a method of straightening the windmill, and then encasing it in plywood to hold it fast as a solid structure.

He then wrote a report, drew diagrams, and built a model showing how he thought the windmill could be saved. Christopher arranged to present his findings to a meeting of the HWBG. Barbara and Christopher (then aged 29 and 35 respectively) thought they would not be treated seriously by the elders of the group. However, apparently they were made very welcome and it was not long before all were enthusiastic about the solutions offered.

He had then committed himself to working on the windmill every Sunday for the next 15 years. The work was started in 1971, and Christopher was responsible for finding volunteers to assist with the work all year round. Some would have the required skills, others would be taught by each other and by Christopher, who ran the whole project as Chief Engineer. The project was greatly assisted by using many recycled materials, and borrowing machinery when required. Christopher was able to develop his restoration theories of replacing as little material as possible, and always finding the best substitute for parts that did need replacing. The restoration of Lacey Green windmill was awarded Wycombe District Council's Malcolm Dean Design Award in 1986.

As the restoration of Lacey Green Windmill progressed, it became evident that Christopher Wallis had managed to combine many talents. There was his inherited talent in innovation, his knowledge of timber technology, his skills in carpentry, and his expertise in civil engineering. These had all combined with his infectious enthusiasm and talent for encouraging volunteers to get involved and give their time. He was always adamant that the restoration was thanks to the whole team who had worked through all the extremes of Lacey Green weather. However, everybody knew that without Christopher's vision and abilities, the whole project would never have begun.

After a few years, Christopher realised that he should not devote just his weekends to preserving historic buildings, but also his working life as well. After 9 years in partnership, he preferred to work on his own, calling on other like minded independent people, and friends, when he needed assistance with heavy work.

Windmills, Watermills and Barns were his chief passions, but he worked on a vast range of properties. Here I would like to just show you some examples of the diverse range of structures that he has helped to restore or preserve.

He has worked on more than 20 windmills, including Bourn in Cambridgeshire, for which he received a Europa Nostra Award in 1986. Over the last few years he has done much work to Wheatley windmill, and to me, the new cap he built at his workshop is a truly beautiful piece of carpentry work. For many years he paid regular attention to a windmill on Paul McCartney's estate in Sussex. As a volunteer he has been involved with the rebuilding of Chinnor windmill for many years.

He has worked on many watermills across England and Wales, in recent years he has been making weekly visits to a watermill at Stanway in Gloucestershire. He constructed a new waterwheel for the Centre for Alternative Technology near Machynlleth. To be strictly accurate, he made the 10 foot wheel in his back garden, and then adapted a trailer to transport the waterwheel to Wales. He did a vast amount of other work to promote alternative technologies.

He also worked on many barns and other farm buildings over a wide area, including the large barn at Pitstone Green Farm Museum, and the re-erection of some at the Chiltern Open Air Museum. One barn he reconstructed won an award from the Country Landowners Association. He tackled many projects on houses and cottages, just one example being the property now occupied by the Amersham Museum. Together with friends he also took on the job of restoring a very old Welsh cottage, which used to be the holiday home of a relative.

He restored structures at country houses, such as the dovecot at Chicheley, an icehouse at Bisham, and medieval fishponds on Lord Heseltine's estate. He also worked on features at many National Trust properties, including the cascade at West Wycombe, walls at Ashridge, and bridges and sluices on the water features at Stowe. He would fearlessly try to get many machines or waterwheels working, which had stood idle for up to a century. Some of these projects involved organising teams of volunteers who helped with the work, in turn, some of them would become experts and life-long friends of Christopher.

A unique project he tackled was the restoration of the last surviving 18th century flashlock capstan on the Thames near Medmenham lock. For this work he won Wycombe District Council's Jack Scruton Heritage Award. Another unusual item he built was a rotating seat, housed in a large barrel, in Gilbert White's garden at Selborne in Hampshire, and used for observing wildlife. He got involved in many small projects, such as village notice boards, which means that there are examples of his craftsmanship across the Chilterns that he loved so much. In 1990 he was made a member of the Institute of Carpenters.

Another interest of Christopher's was transport. His career with British Rail ended when he proved official reports wrong about supposed insect damage to the timbers of the Barmouth Viaduct. His own report in 1981 enabled the Cambrian railway line to remain open from Shrewsbury to Pwlhelli. His engineering skill was also instrumental at a public enquiry over the closure of the Settle to Carlisle railway line. The evidence he gathered himself on the Ribblehead Viaduct was a vital part of the decision that enabled the line to stay open. He produced many other ideas to improve and maintain transport links, such as a footbridge attached to the railway bridge at Bourne End to form part of the Thames Path. Locally he campaigned for the re-opening of the Bourne End to High Wycombe railway. He also produced many ideas for improving proposed road layouts, particularly to try and make them better for pedestrians and cyclists. He worked closely with the High Wycombe Society on these local matters. He also worked on new bridges for the Sustrans network of cycle paths, particularly in Wales. The modern idea of sustainability is the type of principle that had long been obvious and completely natural to Christopher. His own favourite form of transport was a bicycle, which he would try to use whenever possible, even if starting a journey by train, which he and Barbara would do every September for the Historic Churches Bike Ride.

I have to mention that Christopher held some very strong opinions, and was never frightened to speak his mind. On many occasions this would lead to some very heated debates, which could be disconcerting for some people. His strongest opinions concerned his aversion to the conversion of barns for domestic use, in fact readers of the Chiltern News will realise that the latest round of that particular debate had been started in an article of Christopher's in the March 2006 issue, published just 10 weeks before he died.

Since attending their first meeting of the Chiltern Society's Historic Works and Buildings Group, in 1968, Christopher and Barbara remained key members of the group. They not only organised various projects over the years, but have both held office as Chairman of the Group at different times. When Christopher was 65, he told the Lacey Green Windmill Committee that he had retired, and would be able to take life easy. Of course, he continued to take on a long stream of projects and would never have stopped working at all. He only seemed to slow down when he could spend time with any of his four grandchildren. He had seen his father working until he died in 1979 at the age of 92. Christopher had certainly inherited the same dedication to work, and he kept working until four weeks before he died.

Christopher always preferred to be known as himself, and for his own work, rather than that of his father. It is undeniable though, that he inherited his father's incredible enthusiasm for work. After Sir Barnes Wallis's death, Christopher became involved with various projects that commemorated his father's life and work. However he was always rather frustrated that the media always tended to concentrate on the Bouncing Bomb as his father's greatest achievement. They tended to ignore other inventions and designs, such as the totally successful R80 and R100 airships, geodetic structures for aircraft wings and fuselages, the Wellington bomber (of which over 11,000 were built), development work for swing wing aircraft, and using his skill as 'the master of light structures' for developing items such as improved leg callipers. Sir Barnes also continued his original work with marine engineering, and helped develop radio telescopes, as well as spending much time and money in work for charities and improving education.

Sir Barnes Wallis was often described as an eccentric and largely self-taught man. His son Christopher surely took after him in those ways. However, his priorities were different, whilst his father was designing giant leaps forward in aviation technology, as a boy Christopher imagined he would be quite content to become the Village Carpenter. However, he would come to spend half his life preserving the work of carpenters and other craftsmen from previous centuries. He had a full understanding of traditional skills, materials, and tools, and was experienced in using them all. However, he fully appreciated that all techniques were constantly evolving, and he was not afraid of using modern glues or other materials, or modern power tools when there were obvious advantages. His main criteria would be that all work, and the way it was done, had to be appropriate to respect the work of his predecessors, such as the carpenters who he regarded as 'giants' of their time.

The work that Christopher achieved was always more important to him than any financial gain. He cared deeply for his family, but as long as they were healthy and well fed, best of all with food from his own allotment, then he was happy. He had his own allotment from 1970, and later became the manager of the local allotment site. Christopher lived all his life without any personal need for television or computers, or indeed much technology at all, a radio was sufficient for his entertainment, and The Guardian kept him in touch with the world. In fact he often hated the spread of technology, especially when it had an impact on the historic environment. For example, amongst the many letters he would write to the press, in recent years he strongly objected to ideas that church towers should be used for housing mobile phone transmitters.

In the 22 years that I knew Christopher, I would see him become annoyed at press reports he would read about 'threatened' pieces of the country's heritage, which would apparently need vast sums of money to put right. They could be whole buildings, or just walls that needed repairs or monuments needing attention. He would take it on himself to survey some of these items, and compile detailed reports showing how things could be put right with far less work and expense than was being predicted. These could be thrust into the hands of owners or local councils, which would result in a variety of responses.

He was very keen that, wherever possible, the buildings he had restored could be seen by other people, to raise their interest and encourage them to value old buildings more, and hopefully get involved in fighting for their preservation, whether by campaigning, or actually tackling the work themselves. I know myself that many visitors to Lacey Green Windmill are inspired by what they see, and will often leave with a much greater appreciation for the type of historic buildings that Christopher fought to preserve.

Since his death, there have been many tributes paid to Christopher Wallis, including some in the local and national press, specialised journals and newsletters of organisations with which he was involved.

On 21st July 2006 a Memorial Service for Christopher was held at St John the Baptist's church, Little Marlow. This was appropriately another building on which Christopher had worked, repairing and strengthening the bell frame within the last few years of his life. The bells had been silent for many years, but they were able to ring to announce Christopher's Memorial Service.

Attending the service was a truly remarkable experience, it brought together all aspects of Christopher's life. Many only knew him through one of his particular interests or individual projects on which he worked, but all the major phases of his life were presented to us by the people who had become his life-long friends over the 71 years of his life.

There was the boy next door with whom Christopher built tree-houses in the garden at Effingham, at a time when Christopher's father would have been working on famous projects for the war effort. There was a colleague from boarding school, and another from university. They spoke of Christopher's adventurous spirit, of his determined nature, and of unforgettable voyages and holidays, including mountain climbing trips, that they made with him.

Then there were three who had worked with him, in the great variety of restoration projects that he had tackled. They spoke of Christopher being a remarkable engineer, and of how he was able to explain his ideas and theories to people in simple terms, using models when required. They all felt privileged to have known him, and spoke of how he had inspired them all. They mentioned his philosophies, such as always seeking out the most appropriate materials, and in keeping the evidence of work done in the past, but they also all seemed to agree that there was a tendency for an excess of old materials to accumulate at various locations.

It was very noticeable how Christopher had kept in touch with people from all the different phases of his life These people were proud to call him a good friend, even though they knew he could easily criticise them, such as the one who had arrived late at the service due to delays on the M4, and could well imagine Christopher telling him "You should have come by train".

We also heard from Christopher's sister Mary, who was 8 years older than him. She said he always had an independent and sturdy character, but she also told of his musical interest, and his viola playing and singing which was highly regarded.

Humphrey and Amy, and Erica the eldest grandchild, all spoke of his family life, the vital part of his personal life. Whilst it was also obvious that he could be just as outspoken with his own family as with other people, and they showed that whilst they had never been spoilt by Christopher, they had been encouraged and supported by him, for taking whatever paths they chose in their lives.

The reminiscences about Christopher were interspersed by music from a string quartet, readings, singing, and some well known hymns. During the 90 minute service the temperature inside the church rapidly increased, with around 300 people packed in on a very hot afternoon, but I am certain that no-one there would have wanted to miss the experience.

After the service, the local cricket pavilion (again a building on which Christopher had worked) was the venue for the sort of perfect and generous tea that only the local WI could provide. People were able to view a collection of photographs of Christopher's family life, as well as photos and press cuttings about his work. Also on display were some intricate wooden models of different projects which Christopher had made to help people understand how his schemes and theories were possible.

As Barbara had hoped at the beginning of the afternoon, people were then able to chat about their memories of Christopher and his work, everybody having their favourite tales of how he and his work had made a significant impact on their lives.

However, of all the words spoken and written about Christopher since he died, the simplest yet most fitting tribute must be from his family's announcement of his death on 10th May 2006:

Loving husband of Barbara, father of Humphrey and Amy, grandfather of Erica, Daniel, Grace and Silas. Restorer of windmills, watermills and anything that needed 'hands and brain'. He will be greatly missed.

Christopher Wallis in October 2005, seven months before he died.

This page ( cw-obit.php ) was last updated on 21 February 2018.

The Chiltern Society is a Registered Charity No 1085163 and a Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in England and Wales Registration No 4138448.